The Movement of Forgiveness

“Far from being the pious injunction of a Utopian dreamer, the command to love one’s enemy is an absolute necessity for our survival. Love even for enemies is the key to the solution of the problems of our world. Jesus is not an impractical idealist: He is a practical realist. . . We must develop and maintain the capacity to forgive. (The One) who is devoid of the power to forgive is devoid of the power to love.” –Martin Luther King, Jr., in Strength to Love (1963)

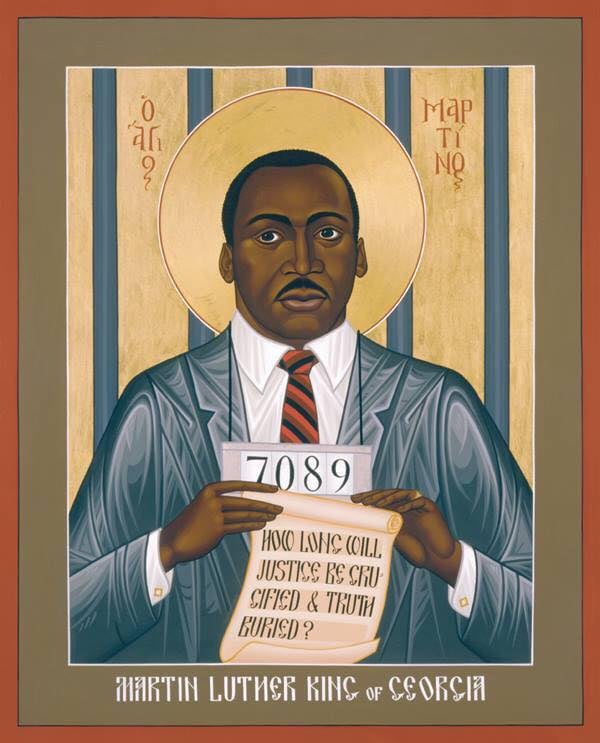

These are strong and challenging words from Dr. King, contained in a published version of his sermon, “Loving Your Enemies.” King posits that while there may be no more difficult admonition from Jesus than the love of enemy, it is “an absolute necessity for our survival.” Our responsibility as followers of Jesus is “to discover the meaning of this command and to seek passionately to live it out in our daily lives.” Indeed, we find it in the midst of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, in Matthew 5:43-48: “You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and he sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. For if you love those who love you, what reward do you have? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? . . . Be complete, therefore, as your Heavenly Father is complete.” Our love is meant to reflect God’s defining, transforming, unbroken love. Forgiveness, Dr. King says, will be the first step necessary if we are to embody such love. Martin Luther King, Jr., Day prompts us to behold and plumb the depths of Dr. King’s ministry and life anew. I want to explore the role of forgiveness in Martin’s ministry and in the Movement.

For him, forgiveness was the breaking of cycles of violence and retribution, in order to open up a future shaped by different forces and possibilities. Forgiveness is an initiative, not a reaction. It will require discipline, creativity, and practice. This is why Dr. King said that it is essential to “develop and maintain” the capacity to forgive.

MLK emphasized that forgiveness is not ignoring an injustice or minimizing an “evil act;” it is not excusing or overlooking a wrong; it is not forgetting. These are common misconceptions. Rather, forgiveness means acting in a way that the injury will not be allowed to dictate the future. In New Testament terminology, it can be the lifting of a burden or the canceling of a debt. Forgiveness can begin to create space and opportunity for new history to emerge from even a tortured past. King equated forgiveness with reconciliation, and while I would agree that forgiveness can lead to reconciliation, I do not agree that they are one in the same. In his Loving Your Enemies sermon, King often uses conditional language that can sound absolute. The “creative, redemptive goodwill” that he and the Movement seek to incarnate is much more pliable and textured. From the ongoing history of the Movement itself we can behold the multifaceted nature of such for-giveness, and King’s invitation to “discover the meaning of this command and seek passionately to live it out in our daily lives” is the territory of discipleship.

With King, the practices of forgiveness and enemy-love begin with inner work. This is what he is referring to when he speaks of developing and maintaining capacity. In The Forgiveness Lab, I would call this “living as a forgiven person.” The realization and exploration of our own “forgiven-ness” can be powerful inspiration. Both SCLC and SNCC engaged highly developed practices of reflection and discernment. SNCC leadership meetings could take days. SCLC leadership meetings reflected King’s work in community-building with the movements own leaders, who were often striving with one another. He saw the gift in each of them, and nurtured the capacity among them to see each other in much the same way. On a broader scale, SCLC direct action campaigns confronting racial injustice required anyone who was going to participate to be trained in nonviolence. This was all profoundly spiritual while being deeply practical as well. As Dr. King said in one of the earliest versions of this sermon, back in his church in Montgomery, “Jesus wasn’t playing.”

The practice of forgiveness continues in humanizing the “other,” whom Martin refers to stirringly as the “enemy/neighbor.” The egregious acts someone commits or participates, the hurts that they inflict, are never the full expression of who they are. King, like Jesus, invites his followers to identify with the other party in the ruptured relationship. “When we look beneath the surface, beneath the impulsive evil deed . . . we recognize his hate grows out of fear, pride, ignorance, prejudice, and misunderstanding, but in spite of this, we know God’s image is ineffably etched in his being.” There is an invitation to recognize that such forces have manifested at different times in our own lives. Love and understanding for others can yield a harvest of self-love and self-understanding. Recognizing the image of God in them, and affirming it in ourselves, leads to a very careful commitment to doing unto others only what we would seek or accept from someone else. It is important not to seek to humiliate the other or to perceive even righteous struggles in terms of conquest: “Every word and deed must contribute to an understanding with the enemy and release those vast reservoirs of goodwill which have been blocked by impenetrable walls of hate.”

The Movement embodied the message. Dr. King’s powerful oratory translated the mission vividly: “I say to myself, hate is too great a burden to bear. Somehow we must be able to stand up before our most bitter opponents and say: “We will match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will, and we will still love you. We cannot in all conscience obey your unjust laws obey your unjust laws and abide by the unjust system, because noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good so throw us in jail and we will still love you . . . Send your propaganda agents around the country, and make it appear we are not fit, culturally or otherwise, for integration, and we will still love you. But be assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one day we will win our freedom. We will not only win it for ourselves; we will so appeal to your heart that and conscience that we win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.”

King is describing a Movement of Forgiveness, one that is defined by agape love, one that does not violate the discipline of that love as it is applied to the opponent. It is an initiative, not a reaction. It breaks the cycles of violence and diminishment, and recognizes the image of God in all people. The temptations of bitterness and retaliation are overcome, as they will just duplicate the old order. Here, the means and the desired end cohere. There is the promise of transformation. In every step, opportunities for dialogue, mutual respect, cultural transformation, and new life are offered. The future will be built on a different foundation, beginning to emerge from the outset, enacting the good news of God’s saving love and its implications for everyone. The Beloved Community will be an in-group for all people, or it will not manifest the Reign of God.

In the Movement, these were all “down-to-earth” and authentic, real-life translations of the gospel of Jesus Christ, embodied in Montgomery, in Albany, in Project C and the Children’s Marches in Birmingham, in Selma, in Chicago, in Memphis. They were embodied beyond SCLC, in the SNCC campaigns to register blacks for voting in the deep South, in community organizing and building over years of time, in learning from local people and the sages among them, in the Freedom Rides and the Mississippi Freedom Schools. In returning to Memphis, Martin refused to break solidarity with garbage workers there, even with the demands of the coming Poor Peoples March that his staff thought was more important. King was deeply upset when discipline in an initial march had broken down among those who had not submitted to the nonviolence training. The next march would be an important expression not only of love but repentance by SCLC. This is the commitment of such “give-ness!”

A striking characteristic of all forgiveness, one that is specifically reverenced in King’s oratory and movement, is fidelity to the truth. People often mistake forgiveness as the denial or setting aside of truth. The agape discipline of the direct-action campaigns laid bare the violence and brutality of the prevailing order, exposed in plain sight the deathly lies on which injustice was built and maintained. And in the manner of Jesus in the synagogue in Capernaum (Mark 1:21-28), the movement manifested the ability to distinguish between the “unclean spirits” that twisted the unjust or spiritually paralyzed, and the deep humanity of each (even when obscured). For a dose of uncomfortable but hopeful truth, take time to read the text of King’s Letter From the Birmingham Jail, written from a jail cell in the midst of that campaign. Smuggled out on newspaper pages and other scraps, King addresses the missive not to Bull Connor or the KKK, but to pastors who considered themselves progressive (the “liberals”) but who prevailed upon King and the movement to cease their efforts as they were “untimely.” Speaking collegially, King said that in his experience, in terms of justice, “Wait” has almost always meant “Never.” He speaks clearly: “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s greatest stumbling block in the stride toward freedom is not White Citizen’s Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate who is more devoted to order than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says, “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I can’t agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically feels he can set a timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by the myth of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait until a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.” Forgiveness, in the receiving and the giving, is never shallow! The Birmingham Epistle becomes a fresh invitation to be “co-workers with God.”

There is much here for continued reflection and application. On MLK, Jr, Day, I love once again digging beneath the endless images of King on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial and the shameless proof-texting about “content of character,” to listen and discern the deep lessons of my fellow pastor and God’s often-sharp tongued prophet. And hopefully to continue learning the communal lessons of a whole movement and its fidelity to God’s enduring, transforming, saving love. Did you know that before his stirring vision of the descendants of the enslaved and the descendants of the enslavers sharing the same table of communion, Dr. King called strongly for reparations in the wake of historical injustice, stating clearly that the “promissory note” the founders had promised for all Americans had come back to black citizens as a “bad check, marked ‘insufficient funds,” and it was (is) time to make it whole. Ah, forgiveness and reconciliation, together!

Sources:

Martin Luther King, Jr. “Loving Your Enemies”, in Strength to Love. Fortress Press, 1981, pp. 49-57.

Martin Luther King, Jr. “Christmas Sermon on Peace,” in A Testament of Hope. (edited by James M. Washington). HarperCollins, 1991, pp.253-258.

Martin Luther King, Jr. “Letter From the Birmingham City Jail”, in A Testament of Hope, pp. 289-302.

Martin Luther King, Jr. “Loving Your Enemies,” Sermon Delivered at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, November 17, 1957, archived at The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and education Institute, Stanford University.