Applying God’s Forgiveness to the Sin of Racism

Some of the Pharisees near him said to him, “Surely we are not blind, are we?” Jesus said to them, “If you were blind, you would not have sin. But now that you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains. –John 9:40-41

Those of us who are white Christians in America need to accept God’s forgiveness for the persistent racism of our dominant culture and for our collusion and participation in its destructive and devastating impact on countless human lives and whole generations of people. As a pastor, I believe that the church is particularly situated to take the lead in this process of transformation within our society. Recognizing that God’s for-giveness is the gracious, unilateral power that removes seemingly immovable obstacles, that lifts crushing burdens, that loosens chains that bind, and sets people free, we can expect that God is already removing the lifeless excuses, lifting the weight of internalized guilt, loosening the grip of our fear, opening our eyes and hearts to those we have not yet embraced as sisters and brothers, and freeing us to respond with our whole selves. These are acts of love. We in Christ’s church are called to meet God’s challenge vulnerably, confessionally, and with a desire to repent. As people of the gospel, we will trust God’s promises, counting on the Holy Spirit to enliven us in this endeavor.

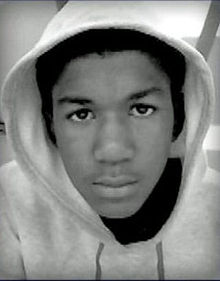

The killing of teenager Trayvon Martin in Florida and subsequent acquittal of the man who shot him, George Zimmerman, has brought the continuing racial division and the unhealed wounds in America front and center. A recently published survey from the Pew Research Center found perspectives of the verdict largely divided along racial lines. This is painful but not surprising. How we see largely depends on our location. In the community where I live, many good and decent people cannot understand protests against the outcome.

“Explaining Black Pain in Light of the Zimmerman Verdict” is Reverend Drew Hart’s powerfully articulated response to a request that he help explain the pain, anger, and frustration over the Zimmerman verdict from within the African American community. I recommend a full and careful listening. From the second paragraph: “Therefore, what seems obvious to those within the black community, and to many people around the world who have watched this case with deep curiosity, still remains blurry for many who are part a part of the dominant culture and have the privilege of not needing to understand the deep ongoing pains and concerns of the only people group in America to be brought to this land not seeking freedom but rather bound by dehumanizing chains of American chattel slavery. To not know or care about the actual frustrations of African Americans, and to choose to make straw men arguments rather than to be disciplined in actually hearing the voice of those who cry out, leads us to our current question:”Why are black people responding now with such frustration?”

In light of Drew’s powerful and– if you read it fully– sensitive presentation, I would expand my previous statement to say that both how we see and how we hear depend on our location. Many of us mistakenly think of racism as a personal attitude of hatred or prejudice toward an individual or group because of their color,and we don’t perceive such an attitude in ourselves. But racism is systemic. In the words of Harold Dean Trulear : “Racism is not an individual hatred of a particular race; rather it is a cultural assumption that one race is normal and the other somewhere between derivative and defective. Racism produced “flesh colored” crayons in my elementary school fifty years ago . . .” Bill Wylie-Kellermann is helpful when he describes racism as “prejudice with power behind it.” For those of us entrenched in the dominant culture, these distinctions help explain why, even as many of us believe in principles of human equality and fairness for all people, we behave as though blind to the realities of mass incarceration of African Americans, the widespread and persistent racial profiling, discriminatory practices like New York City’s “stop and frisk” law that target minorities, the continuing and devastating rates of poverty and unemployment that impact communities of color disproportionately, the persistent patterns of racial segregation that remain half a century after national civil rights legislation. These are obvious injustices in considerable public view. How is it that we will not recognize them for what they are?

In the ninth chapter of John’s gospel (vv. 1-41), Jesus encounters a young man whose marginalization was assigned “from birth.” His poverty, social station, perceived deficiency, and labeled identity are all attributable to sin, say Jesus’ disciples. “Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born this way?” Of course Jesus’ disciples, though they are in close physical proximity to the man, never speak to him directly. Instead, they engage in a theological assessment of his worthiness, a discussion that the man can hear but is not invited to participate in. The cruelty of all this seems obvious, though not to them; the making of such judgments is apparently a familiar and acceptable enterprise. “So did he bring this on himself, or was it bad parenting?” Covering these judgments with a religious veil is particularly blasphemous, ascribing to God the same cruelty and an appalling lack of love.

Do you think the disciples are stunned when Jesus responds clearly, “Neither the man nor his parents sinned”? There is no distance between him and God, Jesus says. In fact, God’s works will be revealed in him, from right where he is. God’s nearness, seemingly hidden from the disciples’ eyes, is right there, in the young man! Now the light will truly shine in the darkness. And it is a far broader “blindness” that will be addressed.

Jesus’ earthy act of giving becomes a kind of anointing . In contrast to the “chasm ” that the young man experiences with the disciples ( a “great gulf” –see Luke 16), Jesus’ relationship with him is personal and touching. The soil of God’s ever creative intent mixes naturally with the saliva of the Living Word and is applied carefully, respectfully, to the body of God’s Beloved. That respect and intent are made visible as Jesus “sends” him to the pool, the healing place named “Sent.” And when the young man returns it is with new vision, and unrestrained gift; he is a blessing to all those struggling with their own blindness. The people around him are astonished at this new reality that forces them to reconsider their long-held assumptions. It is here that the story becomes particularly instructive for those of us in the dominant culture who, in the wake of Trayvon’s killing, unthinkingly assume there has been nothing wrong with the ways we have been seeing things.

“Isn’t this the beggar?,” the people ask, not knowing what to do when someone’s humanity transcends historic labels and when the person will not remain in their marginalized role. Confusion ensues, with some saying, “Yes, it’s him,” while others insist, ‘It can’t be; it must be someone who looks like him.” Beautifully, the unshackled one speaks for himself, a manifestation of God’s gracious new reality. “I am the man,” he asserts, reminding us of the liberation movement of Memphis sanitation workers in 1968 that has inspired so many since.

The crisis deepens, with the entire system shaking on its unsteady foundation. The people of the neighborhood are unsettled first, unwilling to receive him as a “neighbor.” They confront the young man directly, but only to demand answers about his new found presence. Finding what he has to say unsatisfactory, they drag him before the Pharisees. Perhaps we should be grateful that they don’t slay him in self-defense. The leaders try vainly to fit what is happening into the existing social narrative, brutal and failing as it is. They are consumed with fear, and resort to intimidating not only the young man but his parents. Terrified, the parents assert that their son can indeed speak for himself. “Give glory to God!,” the leaders scream at the young man. He does just that, though not as they prescribe. Responding to their denigration of Jesus’ healing power and its source, he says: “I do not know if he is a sinner. One thing I do know, that though I was blind, now I see.” They insist he retell the story, perhaps hoping to find a weakness or a reason to discredit it, and him. He responds: “I have told you already, and you would not listen.” His witness lays bare their own symptoms.

Then the young man brings some critical questions of his own. The first is: “Why do you want to hear it again?” Is it now your intention to listen more carefully? Shortly before the Zimmerman verdict, I posted on Facebook a thoughtful piece from an African American pastor for whom the Zimmerman trial stirred painful memories of his own extensive history of being profiled and abused by authorities because he was a black male. It is powerful testimony. I suggested it as a must -read. I received a very swift response from someone who stated, “I think a young black man profiled a creepy assed cracker and lost.” It also contained a link to a Rasmussen poll with the title, “More Americans View Blacks as Racist Than Whites, Hispanics.” Where to begin? Should I say that the poll article and its title communicate a basic misunderstanding of the meaning of racism? Or that this is one more example of the dominant group telling marginalized people “how it is” and who they are? What really struck me was that my Facebook friend had no response at all to the poignant sharing and real life experience of the pastor, as though he hadn’t heard any of it. I was reminded of Drew Hart’s powerful words about citizens of the dominant culture “hav(ing) the privilege of not needing to understand.” And Drew’s followup: “To not know or care about the actual frustrations of African Americans, and to choose to make straw men arguments rather than to be disciplined in actually hearing the voice of those crying out,leads us to our current questions.” In spite of my upset over the message, I realized that my daily life has shared much more common territory with my Facebook friend than with the African American pastor or with Trayvon.

The young man touched by Jesus has a second question for his inquisitors, one we might hear as an important question for those of us in the contemporary church as well: Do you also want to become Jesus’ disciples ? We cannot live as Jesus’ disciples while practicing exclusion or marginalization. We cannot follow him where he goes without the risk of our own repentance. We cannot practice the core of gospel teaching while tightly gripping (or being gripped by) privilege.

In John’s account, those who are uncomfortable with these questions react defensively and with considerable anger. Rather than receiving the young man’s humanity and authenticity, they violently double-down, decrying his impurity and reasserting the “facts” of social stratification: “You were born entirely in sins, and are you trying to teach us?” And they drove him out (9:34).

In a dominant narrative, the story would end here. Case closed. But not with Jesus. He hears what has happened and finds the young man. Their life with one another continues, even deepens, as they celebrate together the substance of the love of God. “Lord, I believe!,” the man exclaims, a confession of faith into which he pours all that he is. Jesus declares: “I came into this world for judgment so that those who do not see may see, and those who do not see may become blind (9:39, and read ahead to Acts 9:1-20!).

Some of the excluders nearby hear Jesus’ words and react sarcastically, “Surely we are not blind, are we?” Jesus meets them them right there, in the midst of their furious denial, and responds seriously to their rhetorical question: “If you were blind, you would have no sin. But now that you say, ‘We see,’ your sin remains.” Smarting as the message may leave them, this is a manifestation of forgiveness. Jesus remains completely available to them even while joined with the young man. He offers a concrete and undeserved opportunity to make a way out of (what has been) no way, even at this juncture. It is theirs to embrace.

Racism has rightfully been called “America’s original sin.” Many of the “founders and framers” whose efforts we regularly extol and appeal to were slaveholders. The “all men” in, “All men are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights,” did not include African Americans or Native Americans. Was this blindness or blasphemy? For economic purposes,the Constitution measured the value of an African slave as 3/5th’s of a white citizen. The economic engine of the young nation was built on slave labor and the extermination of native populations. These are facts; and thus racism has been deeply woven into the American enterprise from the beginning. It is no wonder that to struggle with it in 2013 is still to struggle with ourselves.

To affirm this is not to deny subsequent history. The Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments ended legal slavery (outside of prisons) and legalized basic rights and equal protection. The American Civil Rights Movement of the twentieth century ended legal segregation and strengthened voting rights. But throughout that same history we have witnessed and experienced the limitations of law and the doggedly demonic nature of racism. The end of the Civil War was meant to herald a new reality. Yet, following two centuries of slavery on the continent, Reconstruction lasted only twelve years before giving way to Jim Crow, lynching, voter suppression, redlining, segregated schools and neighborhoods, and multiple forms of legal inequality in the south and north. Twelve years. The Civil Rights Movement nonviolently confronted the realities of racism locally and nationally, leading to the passage of the National Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. Yet now, half a century later, a “New Jim Crow” is firmly entrenched and the profitability of a prison-industrial complex that relies on the “cradle to prison pipeline” reveals a contemporary economic engine dependent on a new form of slavery. Voting Rights are under attack once again.”Black men now are always seen with a gaze of suspicion and criminality.” Gated communities of body and spirit abound, defended by legalized forms of violence. And in predominantly white communities, children like Trayvon are not perceived as “our children.” Surely we are not blind are we?”

God forgives our racism. By that I mean that only God’s power overcomes the grip of original sin on us. Forgiveness interrupts, breaks the endlessly recurring cycles of dehumanization, destruction,and diminishment, without and within. A transforming power, its work is always more than reformation. In 2013, we need more than reformation. And deep down, most of us know that. What will it mean for us to accept the healing of this forgiveness?

I stated at the the beginning that I believe that the church is particularly situated for leadership in the midst of the larger culture. Because it is the gospel, the good news of God’s love for all, that is at the heart of our life together. Doc Trulear’s words are important here: ” In order for us as Christians to resist the massive effects of those cultural standards that disparage persons based on race, we must start with an ability to see all humanity created in the image of God, irrespective of cultural stereotypes, systemic discrimination, and persistent segregation, whether de facto or de jure. Affirming the image of God in all human beings, especially those against whom our culture has offered consistent contempt, becomes a theological benchmark for evaluating our capacity to love and to provide just treatment for all.”

Then: “In our valuing of young Black males, Christian faith requires that we see in them the image of God and ask ourselves whether such a theological affirmation would change our response to them.” Go ahead and ask yourself.

Drew Hart writes: “The black community is now looking to see how self professed Christians will respond to a people who are struggling, hurting and continually violated. Will it be a response of solidarity with those on the margins like Jesus exhibited or will it be apathy?” This is a critical choice for all of us “near Jesus” (v. 9:40). And it offers a prayerful, penitential, life-giving path!

— Will we finally renounce the “privilege of not needing to understand,” acknowledging that in God’s realm this is our very deep need?

–Will we work faithfully to develop the discipline of actually hearing the voice of those crying out? How will we learn, and who will help guide us? Will we humbly submit to the wisdom and leadership of others?

–Will we open ourselves to a fuller reading of our common history, where the history is interpreted from the underside? Will we claim the fullness of it in the light of the gospel?

–What authentic relationships, across traditional boundaries, need to be engaged? Grown? Deepened? For folks in my congregation, what might it mean for us to trust the depth of our partnerships with Mt. Nebo and St. John Churches in New Orleans and risk discussing the realities of racism and how our authentic relationships might become manifestations of a new history?

–Accepting God’s forgiveness for racism– individually and in community– will require self examination, clear articulation, and a spirit of confession. Faith community is the place to do this. A powerful example of this can be accessed in this article on polite racism.

–Demonstrating a willingness to repent must include practicing solidarity in confronting the institutions, powers, and principalities of racism in our society. It must involve standing with those victimized,occupying unfamiliar territory, risking the wrath of authorities,opening to new manifestations of friendship,and new self-understandings. It will also include a willingness to ask for forgiveness from people who have been harmed, and to advocate for our society doing the same collectively, in tangible and healing ways.

I then shall live as one who’s been forgiven . . . I am God’s child, and I am not afraid . . . I then shall live as one who’s learned compassion; I’ve been so loved, that I’ll risk loving, too. I know how fear builds walls instead of bridges; I dare to see another’s point of view: And when relationships demand commitment, then I’ll be there to care and follow through. Your kingdom come . . .(Gaither/Sibelius)